By Kate Day

‘I quit.’

It was a common phrase in 2021.

So common, it resounded in workplaces over 47 million times, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Forty-seven million instances of two weeks’ notices handed over, last paychecks received, time off paid out, uniforms returned, badges handed over… and new leaves overturned.

So common, it was uncommon. The ‘quit rate’ of American workers topped out at a 20-year high last November. And there has been much discussion.

Over the past six months, headline after headline has sounded alarm and questioned the meaning of this shift—what it means for the future of work as we know it in America. Meanwhile, the ripple effects have impacted countless industries and experiences, in the service and hospitality industries, in particular. It can be felt in those longer drive-thru waits, the disoriented service, the lengthier hold times, and the new faces at local establishments you’ve frequented for years. Corporate America has reverberated with C-suite execs rethinking their life priorities in light of a global pandemic. It’s a hiring crisis. A cutthroat competition for talent, and, at the end of the day, a massive question mark.

The shift has been dubbed clever monikers including ‘The Great Resignation,’ ‘The Big Quit’, and ‘The Great Reshuffle.’ But whatever you call it, studies are attempting to nail down what drove it.

According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in February, “Overall, about one-in-five non-retired U.S. adults (19%) say they quit a job at some point in 2021, meaning they left by choice and not because they were fired, laid off, or because a temporary job had ended.”

‘I quit.’ But why?

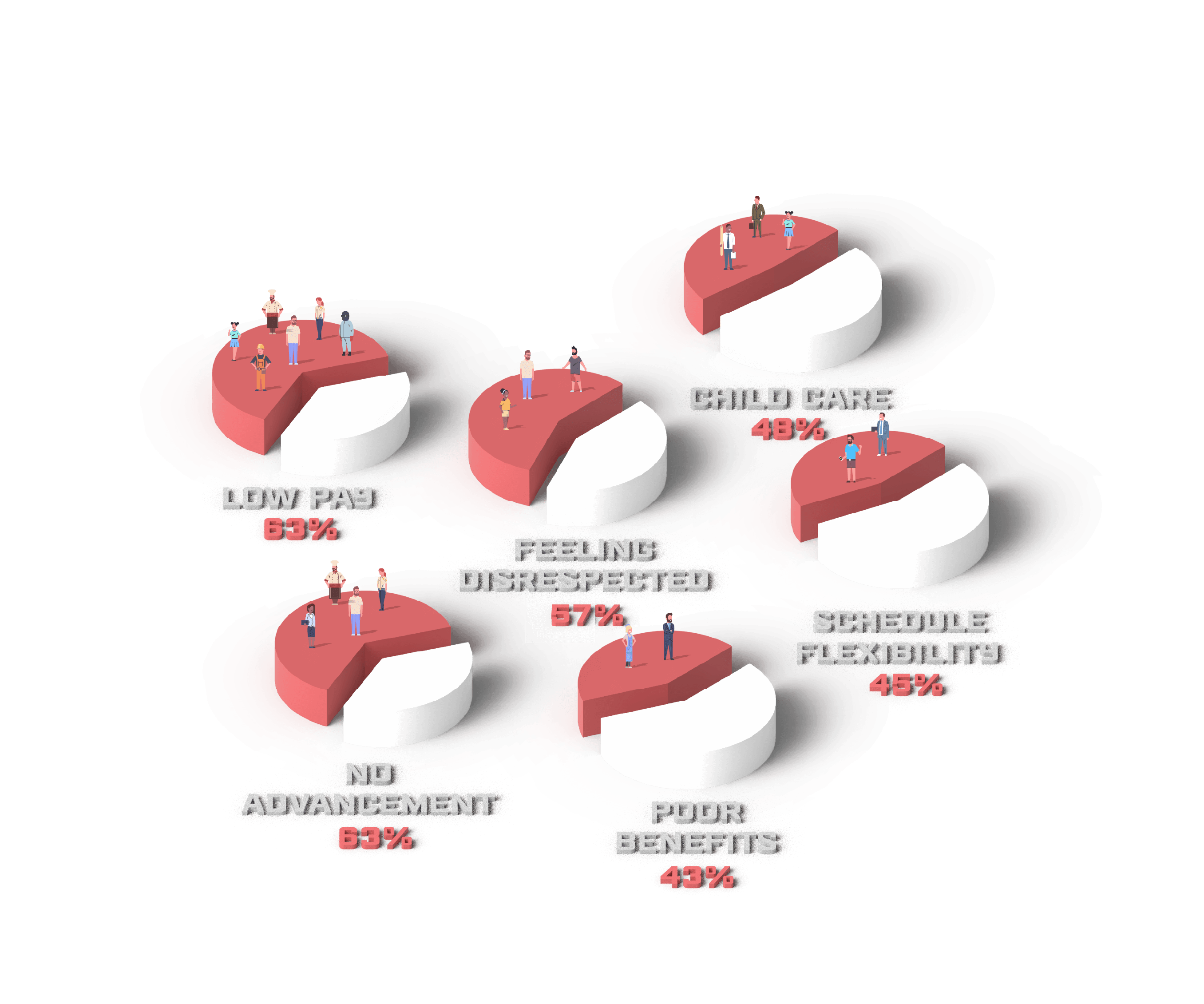

The reasons respondents cited for quitting were all over the map: low pay (63%), no opportunities for advancement (63%), and feeling disrespected at work (57%) were major reasons.

Childcare issues (48% among those with a child younger than 18 in the household), lack of flexibility to choose when they put in their hours (45%), or not having good benefits such as health insurance and paid time off (43%) were secondary.

Other, less dominant factors included working too many hours (39%), working too few hours (30%), a desire to relocate to another area (35%), and COVID-19 vaccine requirements (18%).

An assumption that the pandemic initiated this wildfire of willful transition would be a logical first-blush reaction. However, the research debunks that theory: only 31% of respondents cited the Coronavirus outbreak as being related to their reasons for quitting their job.

‘I quit.’ Why now?

In their March 2022 Harvard Business Review article entitled ‘The Great Resignation Didn’t Start with the Pandemic,’ Joseph Fuller and William Kerr identified five main factors at play in this economic trend: 1) retirement, at accelerated rates and younger ages; 2) relocation, though, oddly, moving within one’s county of residence has remained the most frequent form; 3) reconsideration, fueled by a pandemic-driven perspective shift or burnout; 4) reshuffling, or rather moving among different jobs in the same or between sectors; and 5) reluctance, namely to return the office.

The trick is these factors aren’t new. Fuller and Kerr illustrate the reality of this trend not as short-term turbulence, but rather the continuation of a long-term trend. In keeping with Pew’s findings, they cite all primary reasons for this historic shift were exacerbated by the pandemic, but were already alive and well, progressively impacting the labor market as we know it under the surface of everyday commerce. It simply took a tipping point on the heels of a global pandemic for America to take note.

This latest arresting phase went something like this: Everyone held their breath in 2020. COVID hit. People held on to their jobs. Many who would’ve otherwise quit in 2020, had there been no pandemic, held off. Then, in 2021, the ‘I quits’ were said in double-time. Boom. The tipping point. And now, it’s 2022, and we’re back in line with pre-pandemic quit trends.

‘I quit.’ Wait, who’s ‘I’?

When we start look more closely, and break down the ‘who,’ we gain some insight.

While the results don’t significantly vary by gender, there is another factor that noticeably does: educational attainment. Pew cites those without a four-year college degree (34%) are more likely than those with a bachelor’s degree or more education (21%) to say the pandemic played a role in their decision.

Specifically, respondents with a postgraduate degree are the least likely to say they quit a job at some point in 2021: 13% say this, compared with 17% of those with a bachelor’s degree, 20% of those with some college, and 22% of those with a high school diploma or less education.

The population of adults who quit a job in 2021 without a four-year college degree are more likely than those who quit with at least a bachelor’s degree to cite the following reasons why: not having enough flexibility to decide when they put in their hours (49% of non-college graduates vs. 34% of college graduates), having to work too few hours (35% vs. 17%) and their employer requiring a COVID-19 vaccine (21% vs. 8%).

Among the populations most likely to quit a job in 2021: younger adults and those with lower incomes. Sum total, about a quarter of adults with low incomes say they quit a job in 2021.

‘I quit.’ Now what?

The research indicates that the majority of those who quit a job in 2021 (again, not retired) report now being employed either part-time or full-time. Most of them also report it was reasonably easy to land another job, and that their new job is better than their last job. However, this majority is slight.

The Pew study also tells us that college graduates are more likely than those with less education to say they are now earning more and have more opportunities for advancement, compared to their last gig. The reverse is also true for those surveyed with less education.

For many, their post-quit next step took them to a new field of work or occupation: 53% of employed adults who quit a job in 2021 say that this applies to them. This occupational jump was most common for healthcare and service industry employees, as well as in younger workers as whole. Those younger than 30 and those without a postgraduate degree are especially likely to say they have made this type of change.

‘I quit.’ Oops.

For some, the sixth ‘R’ may be regret. According to a Harris Poll survey conducted for USA TODAY in March, out of around 2,000 U.S. workers who quit their job in the past two years, about one in five said they regretted doing so. Only 26 percent stated they liked it enough to stay, and a third reported they had already begun searching for a new role.

Even some of the quitters, ‘reshufflers’, relocators, and ‘reconsiderers’ are feeling uncertain.

‘They quit.’ What do we do?

If institutions of higher learning ignore this and other research breaking down the phenomenon of at least what has been perceived as ‘The Great Resignation,’ they are failing. That is, we are letting our students down if we aren’t asking this central question: What does it look like for our seniors stepping into this shifting workforce?

Graduating seniors in the class of 2022 have had the vast majority of their college experience disrupted and are not alone in their growing adaptability and tolerance for uncertainty. These are characteristics of the newest wave of workers. Graduation stories everywhere this May reminded us that around two million people will earn a bachelor’s degree from a U.S. college or university this year, and all of them had to overcome unusual circumstances to achieve this. Campus closures, remote and online classes, virtual advising meetings, team projects… an educational obstacle course.

Reports are also indicating that for this group of young adults, the perspective brought about by experiencing the chaos of a global pandemic and all the questions that come with it, perhaps translates into a priority shift when compared to their predecessors. Salaries and benefits are still and always will be important. But a company’s values, culture, and its human-impact quotient are becoming at least as critical to an increasing number of younger workers as their figure on their personal paycheck.

The workplace looks different. ‘Office life’ is relative. The Society for Human Resource Management expects the number of people in U.S. who do more or all of their work from a remote location is expected to double the pre-COVID number, surpassing 36 million.

The workforce looks different. For many, jobs have turned into juggling acts. Census data also indicates that the percentage of U.S. workers holding more than one job at a time has grown steadily over the last decade, another slow-growth trend we’re just now fully realizing.

What does it look like for us to prepare them for this? What does it look like for us to respond to this in our churches? As educational organizations? What does it look like for believers leading workforce? For you, our alumni running small businesses and engaged in industry? For you as parents, supporting your students as they navigate decision-making in an era of work and life that feels foreign to the one you entered? For you, experiencing this shift yourself?

One of the common themes throughout Pew’s research study was the continued value of a college degree. The statistics show that a college degree continues to buffer instability and uncertainty to some degree. That when external factors rocked the boat of commerce, drive-thru lines, and workplace norms in America, those with more education under their belts were more likely to stay put, have more flexibility, and say that even if they did quit, it wasn’t these external factors that were the root issue of their decision to leave their job.

Study after study leaves us with an obvious conclusion: assuring the increasing accessibility of educational opportunities is one of the most worthwhile priorities of our time. In Christian higher education, this means increasingly accessible education and support from a group of believers who are called to see silver linings, to see God’s guiding hand even in ambiguity, and to see Jesus as the model of behavior when it comes to meeting people where they are.

It’s tempting to digest the eyebrow-raising stats and let the knee-jerk reaction settle into a knot in our proverbial belly. To defeatedly assume that we aren’t prepared for a workplace shift, on top of waves of economic uncertainty and ongoing ripple effects from the pandemic. And the world is responding exactly how we’re tempted to.

When we step back from the headlines, as believers, we know, that if we’re doing our jobs—truly caring for our people—we are already prepared for this. That our response should be a continued one, because if we’re doing what we’re called to do—loving people and acting accordingly—the solution is already present. And if we aren’t, that we will move forward with conviction and make it right. The right business decisions mean people are cared for. People first. Always. It’s tough, in a society that so consistently gets things out of order.

If 47 million people quit their job last year, and the primary reasons could’ve been prevented by employers respecting their workers on the job, paying them fairly, supporting their work-life needs, and providing opportunities for advancement, then there has never been a bigger moment in American history for the character, wisdom, and love of authentically-committed believers to help build the workforce of the future.

A Note from the Editorial Team

LeTourneau University’s vision, to claim every workplace in every nation as our mission field and produce graduates who are professionals of ingenuity and Christ-like character and see life's work as a holy calling with eternal impact, requires us to engage in the evolution of the modern workplace. As a part of our 2021-2024 Strategic Plan Mission Critical Objective 4, ‘Campus Culture, Health, & Well-Being,’ we aspire to be a workplace for faculty, staff, and students, that pays close attention to organizational morale, health, and wellness. It is our institutional goal to become a top workplace destination within the East Texas community and exemplify the practices and behaviors that make it a career destination. In acknowledging this goal, we acknowledge our room for improvement, lament the instances in which the biblical standard of care went unmet, and collectively pray for God’s wisdom as we lead a campus of incredible individuals called to this place for a purpose.